Editor’s note — In 1936, W.F. Taylor was interviewed about his business at Mora and his recollection of the windstorm that hit the West End on Jan. 29, 1921.

W.F. Taylor, of Mora, was born in Tennessee in 1862, and lived there until he was grown. He spent some years in South Dakota and Montana before coming west to Seattle in 1897. The following year he bought the store at Mora and for a number of years enjoyed a large business supplying the needs of settlers along the Quillayute, Calawah and Bogachiel rivers.

His stock, obtained principally in Seattle, was shipped by small steamers to the mouth of the Quillayute where Mr. Taylor’s store was located. Many of the settlers living far back in the inland, because of the difficulty of making their shopping trips to Mora, bought supplies in what today would seem very large quantities.

A bill of goods including such quantities as the following was not uncommon:

5 barrels whole wheat flour

5 barrels white flour

500 pounds sugar

150 pounds coffee

200 pounds salt

10 cases tomatoes (240 cans)

20 yards denim

50 yards calico

25 pounds chewing tobacco

25 pounds smoking tobacco

This supply was estimated to last six months. Trade was brisk because stores were few and far apart, and at that time every quarter section of land had a settler. But business decreased as the settlers, discouraged by the immense jog of clearing, either deserted their claims or sold out to the big timber concerns which sought all available timberland for logging. The great wind storm of 1921 drove hundreds of settlers away, for in many places every standing tree was blown down and the land then had no real value.

Of the great wind storm of 1921, Mr. Taylor had a clear and vivid recollection. On that January day, with a mild winter temperature, Taylor and his son were engaged in building a shed across the road from the store.

About mid-afternoon the atmosphere grew very heavy and a strange darkness fell over all. From the ocean sprang a cold wind, and the wind and darkness combined to caused the men to cease their work. They returned to the store and started a fire in the big stove and stood around it, discussing the impending storm.

A little later the storm struck. It became pitch dark: rain fell in torrents and the wind was very strong. Sudden gusts bellied in the back of the store and water entered through cracks between the boards as if thrown by buckets. The men could hear sheds in being blown down, but dared not leave their shelter.

A little later the storm struck. It became pitch dark: rain fell in torrents and the wind was very strong. Sudden gusts bellied in the back of the store and water entered through cracks between the boards as if thrown by buckets. The men could hear sheds in being blown down, but dared not leave their shelter.Outside they could see nothing, the darkness was impenetrable. But a terrifying roar told of the falling trees all around. By the middle of the night the storm had passed. In the darkness they could not see what damage had been done, though they were compelled to crawl over many fallen trees on their way home.

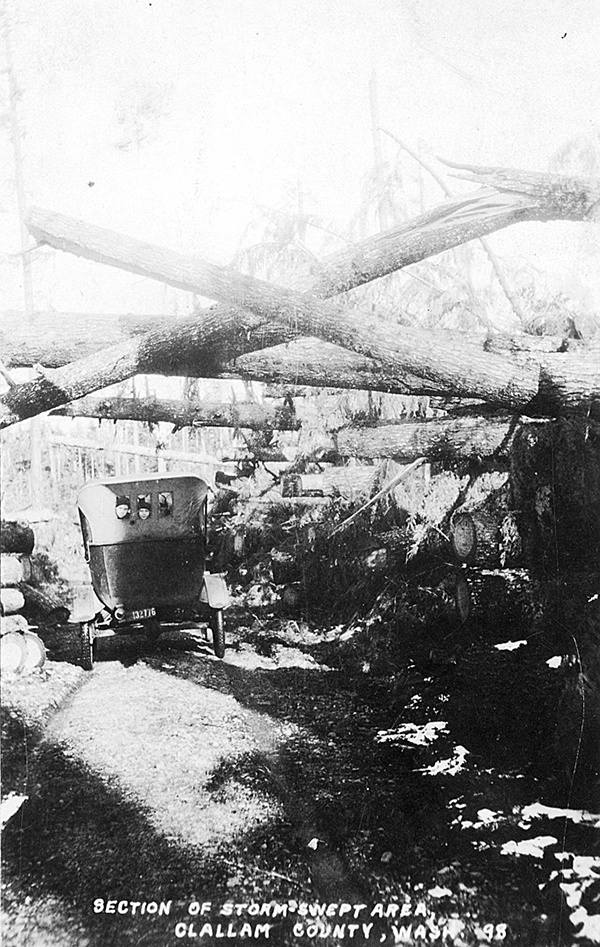

The next morning there was desolation everywhere. As far as the eye could see, where the day before had been covered with great trees, some 250 feet tall, not a tree was standing. The forest was a mass of twisted, torn wreckage, the streams choked.

Strangely, few buildings were greatly damaged. A truck driver who had left the store sometime before the storm broke had got half way home when a tree blew down and blocked the road ahead. With some difficulty he got turned around to start back for Mora but another tree blocked the return. So he went on foot.

The next day he returned to his truck and found it completely hemmed in on all sides by trees, none of which had fallen on the truck. It was 10 days before the road was cleared and the truck brought out.

Taylor felt the storm came ashore near Aberdeen, followed along the Pacific coast to Cape Flattery and jumped across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Vancouver Island, laying waste to timber in one great swath.

In 1936, at the time of the Forks Forum interview, Mr. Taylor, with his wife and daughter, lived at Mora as well as his son and his family. He spent his winters in Arizona where he had a silver mining claim.