By Vera Klock

In the spring of 1942, an army mule train passed through the North Olympic Peninsula on training maneuvers. As far as anyone here can understand, the object of the expedition was to reach the Pacific Ocean. All this was in preparation for jungle warfare in Burma and New Guinea, and mountain warfare in Sicily and Italy. My aunt, Ida (Nylund) Keller, who lived at the north end of Ozette Lake at that time, and whose farm was the last encampment point for the mule train, says that only two men and a mule ever made it to the mouth of the Ozette River – their apparent destination, although some information hints that LaPush was the ultimate destination.

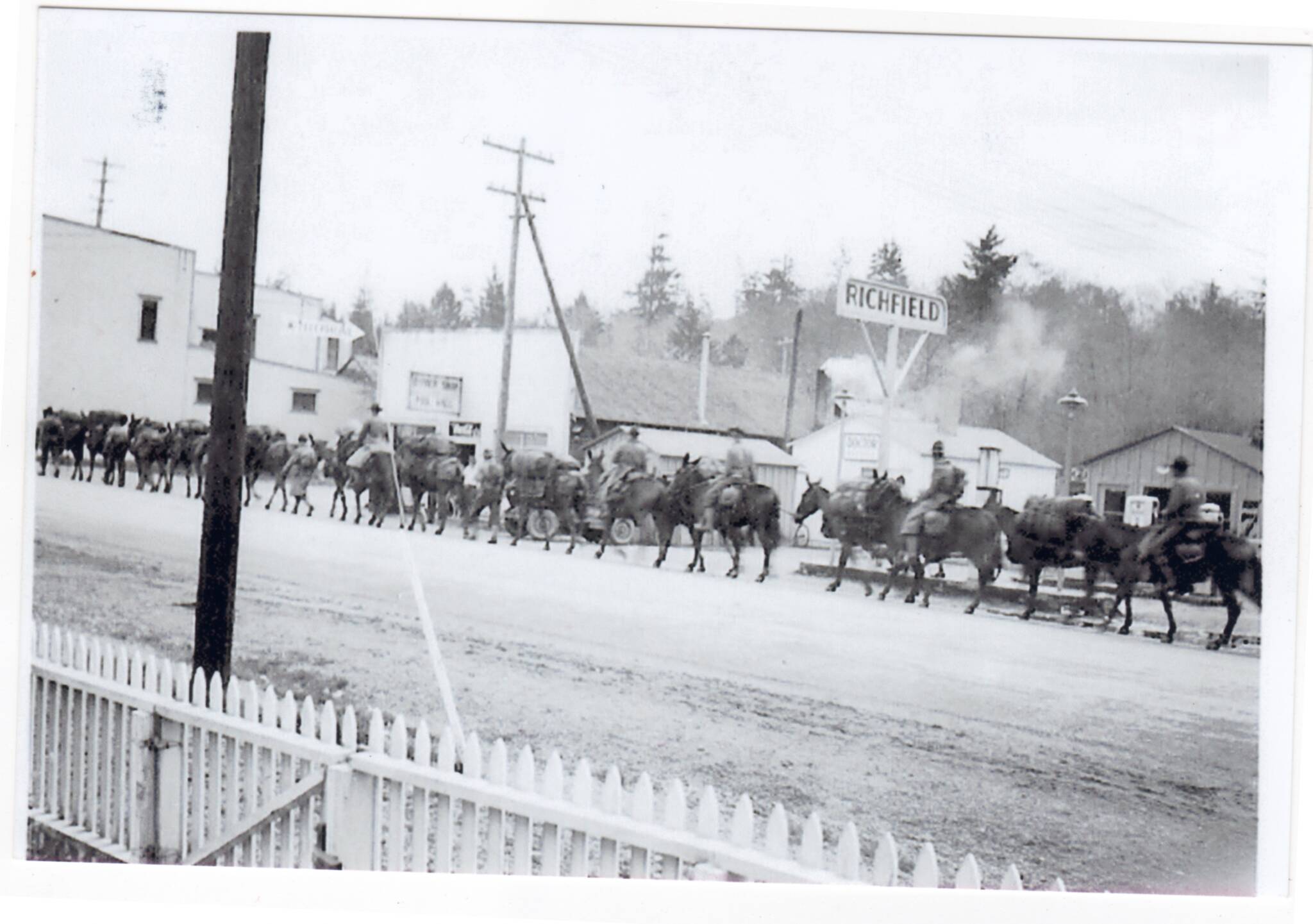

Forty-seven years later (1989), I attempted to write an article about this event for the local weekly newspaper. However, I was never able to obtain any information that would give me the precise dates, facts and figures I needed to build my article. Research at the local library revealed only that little mention of the event was ever noted in the county’s daily newspaper and, of course, being wartime, no pictures were allowed to be taken of anything to do with the military. Larry Burtness has now located a (contraband) photograph of the mule train encampment at Cowan’s Field along the Hoko Road. The pictures are from the collection of Billie Ward, and they were taken from a moving car. (June Bowlby thought that one of the pictures was taken at the Olesen farm, rather than Cowan’s.)

Ethel (Iverson) Dinius, who was a young girl at the time, found an old autograph book with several addresses she acquired when the outfit bivouacked in her stepfather Albert Boe’s field. The date was April 12, 1942, and the units included “Service Battery 98th Field Artillery; Column 1, 174th Infantry, 44th Division; and 56th Medical Division” – all from Fort Lewis, Washington.

It seems likely that the “mule train” was part of the 98th Field Artillery Battalion, and that the other units provided support. Ethel provided a copy of her mother’s diary from for the dates April 12 – 15, 1942.

April 12 Beautiful day

825 mules and 750 soldiers came and camped over night on Albert’s field. It was a wonderful sight to see them all. There were lots of people come to see them. We took the accordion and guitar over and there were some very good players and singers in the bunch. We stayed until about eleven o’clock that night.

April 13 rain

The army all left for Kellers place at the Lake. We went down there in the evening but it was raining too hard to get out of the car. We went to Clallam in the afternoon.

April 14 showers

We had some army men over in the evening. One played the piano swell and one was very good on the accordion. We enjoyed their music and some of them danced.

April 15 showers

From Vera’s notes, Ethel thought that they had arrived about seven o’clock in the morning. and they came in two waves on the same day, only hours apart.”) In a telephone interview, Ethel said she thought that they might have camped the night before at Pysht – at Fernandes (probably Irving’s). She recalled that it took a very short time for the men of the “mule brigade” to set up their camp, with kitchens and latrines (my note says “about 13” – what does that mean? number of tents?) in two of the Boe fields. By the end of that sunny afternoon, her mother was standing at the fence talking Norwegian to a soldier. They had music (accordion and guitar) by the front gate. One soldier sang in Spanish. Her mother and (step)father invited a couple of the men to dinner in the evening; one was probably an officer, the other an enlisted man. Ethel said when they left the next morning, the field was “shining clean,” but they did leave a lot of the oats they didn’t use for the horses. She doesn’t remember seeing the mule train come back.

From local residents, I have been given to understand that about 800 mules, 1000 men, trucks, and a 75mm Howitzer cannon comprised the group that came through the community in two waves. Apparently, they have never forgotten them, for all the hell-raising they did, or forgiven them for introducing the Canadian thistle into the area.

There are several mysteries associated with the travels of the “Mule Train” – how did they get to the Olympic Peninsula, and how did this huge undertaking vanish from the community without a single person seeing them go!

According to Larry Burtness, a Joyce-area informant told him that the mule train disembarked from ships at Port Crescent, where there was an army base (Camp Hayden). She said they camped one night at her family’s farm. This theory does not square with the eyewitness accounts of Claudine Rand and Zoe (Balch) Anderson, who saw the mule train considerably east of Port Crescent – on the streets of Port Angeles, and in front of Dry Creek School, respectively. Both report that the train was headed west.

Virginia Fitzpatrick of the Clallam County Museum noted that several people remembered seeing the mule train pass, including Zoe Anderson, “who stood in the Dry Creek School yard as they went by.” In addition, Virginia’s husband Michael, who was living at Clallam Bay, saw them. His recollection was of a much smaller group than the 800 mules/1000 men Glen Willison claimed.

In a telephone conversation with Zoe (Balch) Anderson on January 8, 2010 (she was ten years old at the time of the mule train), she recalled, “They had big packs on the mules. The horses were ridden by officers beautifully dressed in high leather boots.” The schoolchildren were let out to stand by the fence and watch. It could have been at least a half hour. The men said they were going off to the war; they were all going west, to Port Crescent. She doesn’t recall seeing any black men with the mule train. There was an Army encampment at Zoe’s family’s ranch at Dry Creek was it there before the mule train?

Claudine Rand was married and living in the West End, but she was in Port Angeles on the day the mule train came through there. She said, “We had been told ahead of time (by a neighbor) to go down and watch, and several of us went, and saw them from about the Free Methodist Church at Eighth and Chase until they were out of sight at the Eighth Street Bridge and went on west.” When she saw them, they were coming from Race Street; they didn’t come up Lincoln. Claudine doesn’t remember how long they watched – a half hour to perhaps as long as an hour. The men were “just walking along with the mules”; there were also horses and trucks, and she saw black men as well as white. Claudine doesn’t know why the newspaper wouldn’t have told about this event because people knew about it beforehand, and came to watch.

Bob Bowlby thought that the mule expedition probably camped at Pysht before reaching Clallam Bay. Ethel Dinius believed that they had stayed at the Irving Fernandes’ farm. We know for certain that they camped at Grant Olesen’s (now Barbara [McGuire]Hull’s farm). The picture believed to have been taken at Cowan’s ranch is a bit of a mystery, since none of our local eyewitness recall seeing the mule train there, and there is also a stray piece of information (source unknown) indicating that the train bivouacked at Orsetts, somewhat farther up the Hoko. There is no question that they camped at Boe’s, and their last destination was at the Keller’s farm at the north end of Ozette Lake.

Bob saw the mule train as he was riding his bicycle near Green’s Creek. He said, “When I met that string of guys and mules, they were on a break, so I stopped alongside the road and talked to them for maybe 15 minutes or so… They were friendly.” He just saw the men with the mules. He thought that the trucks must have gone by either earlier or later, because he didn’t see them at that time, only later, in Clallam Bay, he saw the trucks parked, and the black men who were the truck drivers. He described them as “big, long gray International trucks,” and thought that they were for hauling the mules, but others disagreed. Barbara said she saw trucks with canvas over the top, and some men riding in them, but none carrying animals.

Barbara Hull recalled that she was about 12 years old at the time of the mule train. She first saw it when she was on her way to town (Port Angeles) with her father. She said it seemed as though there were miles and miles of horses and mules, and they were moving all the time. The train went single file: “Mule, mule, mule, then a man in a different uniform riding on a horse.” What she really noticed were the beautiful horses. She did not notice that there were black men in the train.

Later, Barbara could see the mule train when it was camped at the Olesens’. She thought that they used both parts of the farm, but Claude Olesen said they took up just one field, the one near what is now Charlie Creek Road. At that time, Barbara’s family (McGuire) was living where Altha Simmons lives now [2010]. The McGuires also rented the Welker place, so they went past the mule train encampment as they drove down Charlie Creek Road to Welkers’ (to do farm chores?), Barbara didn’t even ask to go out in the field to see the mules and horses. She would have liked to, but she knew it wouldn’t have been allowed. After the train left, there were a lot of mule shoes in the field. She used to have many of them; only one is still left. Barbara’s brother George drove a milk truck at the time of the mule train. On his way home one day, he picked up a couple of soldiers who were hitchhiking. When he dropped them off at Olesens’, they forgot a pint of whiskey. (Barbara chuckled when she remembered that, but she is still indignant about the mule train’s trucks bringing cheap hay and creating an infestation of Canadian thistle.)

Claude only recalled white guys with the mules staying at his father’s farm. “When the trucks came in, the black men were driving…. I’m sure they weren’t camped where the mules were camped.” Vera wondered if they served food to the men, or if they just ate “C rations.” Barbara thought they had a big tent set up, and then a lot of little ones for sleeping in.

Claude thought that his father had been contacted by the Army ahead of time; he didn’t know if there had been any compensation. He said there was no way they could have fit a thousand mules into that small field.

Barbara recalled being at school, and going to the classroom windows to watch it pass by. She didn’t remember in which direction the train was going, but thought it was headed west. Local residents recalled that white soldiers walked with their mules while black soldiers rode in trucks; there was much grumbling from the white soldiers. The officers rode horses.

The train carried the Howitzer cannon by mule back – broken down, of course. An article in the Popular Science magazine dated May 1942 describes how the Howitzer was transported by mule. Pictures of the 98th Field Artillery (Pack) Battalion from the Tacoma Library also give historical background on the formation of the unit. According to Don Rand, who was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas in 1942 (and cared for a mule named Sally), the normal pack for a mule was 375 pounds. Army mules had to weigh 900-1100 pounds.

When the men and mules arrived in Clallam Bay, there was conflict between them and local loggers. The mule train soldiers bought up all the liquor and woolen socks as soon as they hit town. According to Charles “Chuck” Evans, “They [the soldiers] were tough and let it be known around town they were tough. The loggers tried to accommodate them, but were no match for them. The loggers were tough too, but these guys were mean. You wouldn’t believe all the stuff that was going on.” Chuck was coming out of Borde’s Drug Store when a bullet went whizzing over his head less than a foot over the door. A second shot was fired, but farther away.

The M.P. was a major and the commanding officer. He carried a 45 caliber Colt automatic pistol. Local logger Howard Storm (“Big Stormy”) was invited by the major into a passageway between the restaurant and hotel. The major said, “You make one move and I’ll blow a hole through you.” Bob Bowlby explained the background of the story he had been told (he wasn’t there), “He and Stormy got into it because Stormy was cruising for a fight, so the major said, ‘Come on,’ and he went ahead of Stormy, and they got back there, and when he [Stormy] came around, he [the major] stuck the 45 in Stormy’s belly and said, ‘You just move, and I’m gonna put a big hole in you.’ That was the end of Stormy’s arrogance. And that story went around town real quick.” (Stormy was a fighter and a logger – until he became a deputy sheriff!)

Bob also corroborated the story Glen Willison told about a black man being shot through the neck. The rest of the blacks then scattered into the swamps. Barbara Hull only remembered hearing about the shooting of the black man, and recalled that the story was that it involved an argument in a local tavern. She said it was thought to have been race-related.

The late Bob Miller recalled the outfit to have been the 98th Field Artillery, “and a renegade outfit.” He believed they were sent to New Guinea. Larry Burtness of Forks says they later disbanded, and 500 volunteers became Army Rangers.

My aunt Ida Keller recalled that the mules were tethered to cedar trees, which killed the trees. The road in front of their home at the north end of Ozette Lake was so deeply rutted it took a long time to bring it back to normal.

(Vera Klock talked to her brother Verne Evans in late December 2009, and asked what he remembered of the mule train. At that time, Verne was living at the family home (originally Alice’s place) near Ozette Lake. He recalled that mules and men travelling from Boe’s farm to his uncle Charlie Keller’s place at Ozette Lake passed the Evans’ place in groups of about 200 for several days. While they were bivouacked at Boe’s farm, he saw a soldier trying to shoe a horse or mule. It was in a pen, to keep it from kicking – which it managed to do anyways, catching the soldier in the face, and cutting him up. He also remembers a truck loaded with hay stuck in a mudhole, and the driver not being able to get it out without extra help from jeeps. Our sister Mary (Petroff) told him that one of the soldiers knocked on her door. When she answered, he asked her, “Do you have any corn squeezing?” – scaring her half to death. Verne remembers that some of the soldiers hung on to their mule’s tail and let the mule pull them along. He recalled that it was so wet at the Keller’s farm that the soldiers walked around with their pipes upside down.

It has been recorded officially that LaPush was the intended destination point, and was achieved, but every local resident I talked to has said, “No.” The mouth of the Ozette River was as far as two men and one mule ever got.

According to an article by Jim Miller entitled “99th FA News” in the July/August 2007 issue of SABER, the 99th Field Artillery 2nd Battalion “was activated June 1, ‘40 at Ft. Lewis, Washington.” It was re-designated December 16, 1940 as the 99th Field Artillery Battalion “and at that time the 2nd Battalion became the 98th Field Artillery Battalion. Later, in ‘43, the 98th FA Battalion became the 6th Ranger Battalion.” However, there is contradictory information in an article about the 6th Ranger Battalion: “The 6th Rangers history begins with a mule-drawn pack artillery unit, the 98th Field Artillery Battalion. The 98th Field Artillery was formed at Camp Carson, Colorado in 1942 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Callicut. According to a history of the development of Fort Carson, “The first shipment of Army mules arrived here by train from Nebraska on July 30, 1942. The men of the 604th and 605th Field Artillery (Pack) had to take the wild mules, break them, and train them to carry a field pack over almost inaccessible terrain. It took six to eight weeks to break and train a mule and the battle could be spectacular.” This history does not mention the 98th Field Artillery Battalion, and the date of arrival of the mules is later than the date of “our” mule train. More research needed!

Jackie Rosen, who interviewed Richard “Dick” Way, a member of the 98th Field Artillery Battalion in Cody, Wyoming in 2004, said that he talked about the training of the mule strings at Pike’s Peak, and the shipping of the mules overseas, and the use of the strings in New Guinea. She didn’t remember anything about Washington. The museum there has duplicates of the information, and will try to get them.

According to an article in Popular Science from May 1942, the unit (the 98th Field Artillery (Pack Battalion at Fort Lewis) “has 500 mules ready to take to the hills with guns and supplies on their backs. And the “muleteers” of the outfit figure they can be just as tough as any mule if any balkiness shows up.” The local estimate of the numbers of men and mules are probably exaggerated. However, there definitely was a 75mm. howitzer with the train. The Popular Science article has two photographs and a description of the method of transport and set up of the gun.

More next week…