Fourteen West End families have shared this heartbreaking experience …It’s the moment every military family dreads. One second, a mother proudly speaks of her child deployed overseas; next, there’s a knock at the door that forever changes everything. That knock, that phrase—“We regret to inform you…” signals a heart-shattering reality: a son, daughter, husband, wife, or parent has made the ultimate sacrifice in service to their country.

Over the course of American history, the way families learn of these losses has evolved, but the pain has remained the same.

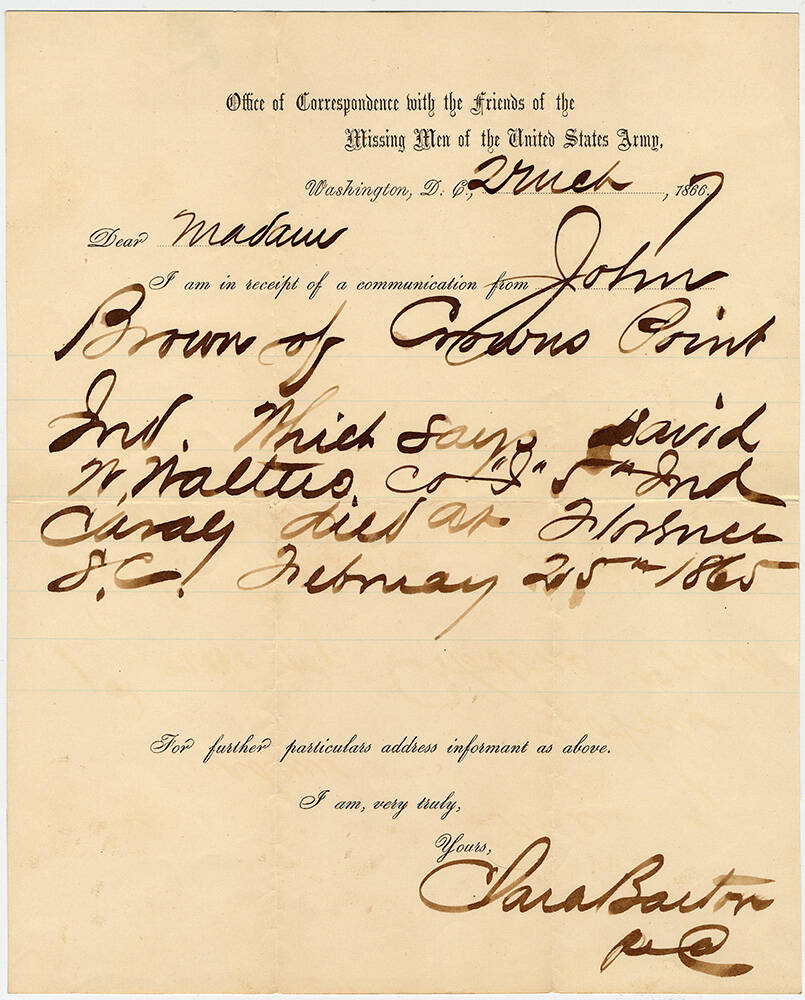

During the Civil War, there was no official system to notify next of kin. Often, the burden fell to fellow soldiers who wrote letters home on behalf of fallen comrades. In many cases, families were left in the dark, with no word at all. The lack of any formal notification led Clara Barton to establish the Missing Soldiers Office in 1865. Working in a Washington, D.C. attic, her organization helped identify over 22,000 soldiers who would have otherwise remained unknown.

By World War II, more structure had formed, but even then, official notification was cold and impersonal. Families would often learn of their loved one’s death through a telegram delivered by a taxi cab driver, an unimaginable moment of confusion and sorrow. Only in rare cases, such as when a family lost multiple members, were military officers or chaplains sent in person.

In October 1944, a policy change ordered all commanders in the war theater to personally write condolence letters to families of those killed under their command, a gesture of humanity in a system that had long lacked it.

Telegrams, efficient, blunt, and devastating, remained the primary means of notification through World War II, Korea, and much of the Vietnam War. Western Union telegrams delivered in cold, standardized phrases, “We regret to inform you…” became infamous symbols of wartime loss. These telegrams often contained word limits, forcing the military to adopt short phrasing that left little room for kindness.

The process finally began to change in 1965, after the Battle of Ia Drang, during the early stages of the Vietnam War. The U.S. Armed Forces created formal casualty-notification teams. These trained officers and chaplains were tasked with delivering the news in person, providing not just the facts, but also immediate support for grieving families.

Today, when a service member dies in the line of duty, accountability is first established in the field. The team’s commanding officer is notified, who then relays the information to the soldier’s base. From there, a carefully trained casualty-notification team is dispatched to the family’s home, aiming to deliver the news with dignity, respect, and care.

But no matter how the news arrives, by telegram, letter, or uniformed officer, the impact is the same. It is the moment war comes home. It is the moment sadness falls on a household.

For those who serve, the battlefield is only part of the sacrifice. For their families, it’s the knock on the door that brings the true cost of war crashing in.

Thanks to all who served and are serving, and all who did not return home.

Christi Baron, Editor