Memories of a former Spartan …

Published 1:30 am Thursday, December 25, 2025

The holidays can be a challenging time for anyone who has lost a friend or relative, at any time, but particularly when that life was taken before its time. Grief is deeply personal. Some people want to talk about their loss, while others try to set it aside, tucking away the reminders as a way to keep moving forward.

This is a story about a life lost too soon, and about memories carefully packed away, placed in a box and hidden in the barn, where they might not be stumbled upon and reopen old wounds.

In 1949, a promising young Forks resident, Allen Crisp, was killed in a car accident. The other three occupants of the vehicle survived; Allen did not. A 1947 Quillayute High School graduate, he had gone on to study zoology at the University of Washington before returning home. At the time of the accident, he was working in the woods.

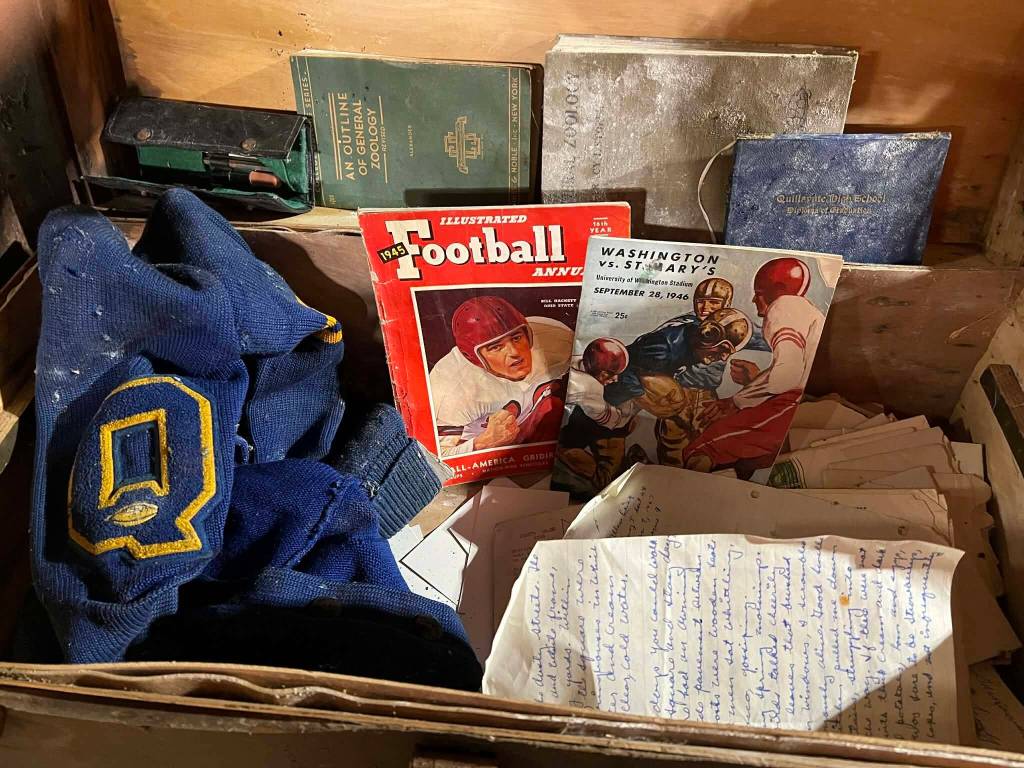

Recently, items from Allen’s short life were discovered boxed away in the family barn: his letterman’s sweater, evidence of his talent as an outstanding football player, his diploma, several college Zoology textbooks, and a heartfelt story he had written during his senior year of high school. In it, he imagined growing up, leaving Forks, and one day coming home again.

This is his story, written in 1947 … that he did not get to live out ….

Homecoming…

By Allen Crisp

As I wandered through the bustling streets, I found it hard to believe that this was my town, the drowsy, easy-going place where I grew up a half-century ago. The cracker-barrel grocery store was now a supermarket. Most of the big trees and fine homes near the square had disappeared. Where once I knew everyone, I was now surrounded by strangers.

I turned away from the hubbub to a side street. Here were houses and pavement where once I raced through open fields. But, around a turn, I came upon one last meadow, and followed a dim path toward the country and springtime.

I plodded up the rise to Fern Hill, which was unchanged from the old days. Lying on the grass in the warm sun, I looked down upon Forks, Washington – the town that was once mine.

When I was a boy here in the 1930s, the sunshine filtering down through the leaves of maple and the limbs of fir trees was bright on the dusty streets. The houses, red brick and wood frame, stood in roomy yards. Within four blocks of the square were farms and springhouses in which crocks of butter and cream rested in the clear, cold water.

On rainy days, you could walk around the square and stay dry, for each store had an awning over the wide streets, and between the outside posts were wooden seats where the old men sat whittling, chewing tobacco, and gossiping.

On sparkling spring mornings, when the birds talked cheerily among the leaves that brushed the bedroom window, I scrambled out of bed, joyously alive! Good smells from the kitchen pulled me downstairs, struggling into clothes along the way. If there were not oatmeal with thick cream and dark sugar, fried potatoes, ham and eggs, then there was sure to be strawberries, hot cakes and not infrequently pie.

Afternoons in summer, I scampered down to the old barn at the end of Joe Wentworth’s lot, where he made ice cream. In spite of the heat I vigorously chopped wood for the engine that turned the freezer, and as a reward, I got the beaters to lick.

Now from Fern Hill at dusk, I heard dogs talking to one another. Years ago I could have identified them – “That’s Mansfield’s dog, Pal” or “There’s old Waggles a-howling.” Now the barks were nameless. And as the electric lights of the town flashed on with the self-confident show of progress and power, only a slight mist preserved the illusion of memories.

I felt that somehow, I no longer belonged here, and for a time, wondered why. Then it dawned on me, “I know what the matter is,” I said aloud. “I am homesick in my own hometown.”